For over a century, reading the brain was framed as a problem of measuring electrical signals at the scalp. And when thinking about brain-computer interfaces, the imagination quickly goes to EEG caps and electrode arrays. But in practice, many interfaces don’t start at the brain at all, or do not even measure electricity. Instead, many modern interfaces start at the body, where neural intent is easier to access once it has propagated into muscles, eyes, and autonomic signals.

A useful way to think about reading neural signals is to focus on where the nervous system is accessed and what is traded off in return. Signals can be captured far from the cortex, such as through muscle activity, or recorded directly on or in the brain, where fidelity is higher but access is more demanding and invasive. Other approaches step outside electrical activity altogether, relying on indirect physiological proxies that provide lower resolutions but can be applied to wider use cases. Each method balances invasiveness, signal quality, setup complexity, and long-term reliability differently.

Surface electromyography (sEMG) sits a step away from the brain, picking up the electrical activity of motor units as neural commands propagate into muscle. It is not a direct cortical signal, but it is tightly coupled to intention, especially in our hands and fingers. The signals are large, fast, and comparatively clean, which makes them easy to capture with electrodes on the forearm or wrist. The result is an inversion of the usual BCI story: instead of struggling to read brain activity through bone and skin, you listen where the signal has already been amplified by the body. With sensitive decoders, you can register sub-threshold muscle activity, making it possible to “type” or gesture without visible movement.

That utility is why sEMG increasingly appears as an input modality. In XR and general computing, it is used to motion clicks, gestures, and text entry by mapping subtle muscle activations to commands. In prosthetics, myoelectric control is a long-standing standard, greatly improving user experience. Pattern-recognition systems allow users to switch grips or degrees of freedom by activating different muscle groups. The main challenge of sEMG is implementation outside controlled conditions. Electrode shift, sweat, fatigue, and changes in arm position all complicate the challenge of going from lab signals to a widespread utility.

.webp)

The companies in this space reflect the different sEMG use cases. Meta Reality Labs, following its CTRL-Labs acquisition, treats sEMG as a future-facing input layer for glasses and XR, integrating motor intent directly into consumer software experiences. Companies like Coapt and Phantom take a more clinical angle, focusing on myoelectric pattern recognition that can be used day after day by prosthesis users. Ottobock, through systems like the bebionic hand, represents the most mature end of the spectrum, where sEMG is a proven interface embedded in real rehabilitation and care processes.

Electroencephalography (EEG) records voltage fluctuations at the scalp generated by large populations of neurons firing in synchrony. Its defining strength is timing: millisecond-level resolution that captures rapid changes in brain activity, making it well suited for tracking states, rhythms, and event-related responses. Because signals pass through cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and skin, spatial detail is limited and amplitudes are small. Much of EEG’s utility comes from careful electrode placement and signal processing rather than raw channel count, with attention to artifacts such as eye movements or facial muscle activity.

These constraints help explain why a small set of paradigms has become dominant in EEG-based tools. Approaches such as steady-state visual evoked potentials and P300-style event responses work by anchoring decoding to neural responses that are already well understood and easy to evoke. Beyond BCIs, EEG appears in a wider range of applications, from consumer neurofeedback and meditation tools to sleep tracking and tools to infer attention or workload. Here, EEG functions more as a measure of brain state than a reading of open-ended intent.

The ecosystem reflects this wide range of EEG applications. EMOTIV offers mobile EEG hardware paired with a software stack aimed at researchers, developers, and prosumers who want usable data without a lab full of equipment. Muse represents the consumer-facing end, where EEG is positioned as a wellness and sleep tracker. Meanwhile g.tec provides clinical and research tools, bridging EEG into more controlled BCI and mapping workflows and offering a natural transition toward surface and intracranial systems.

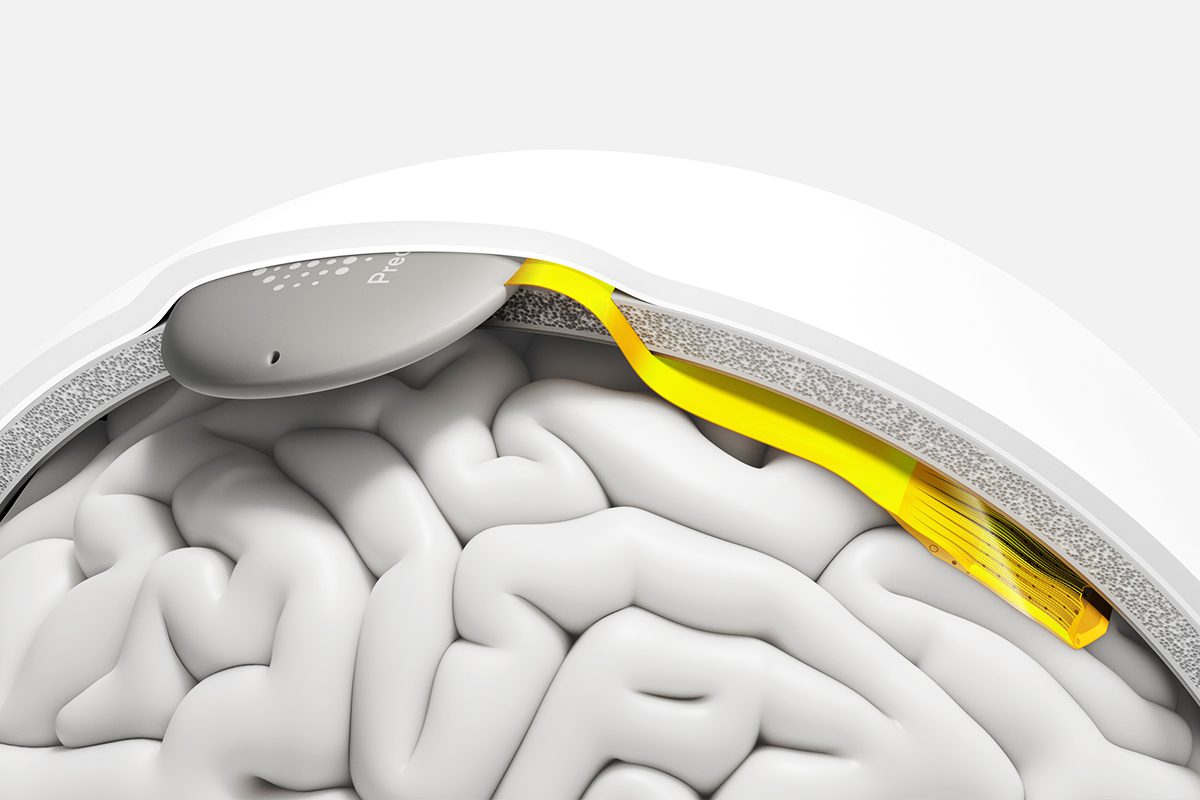

Electrocorticography (ECoG) records electrical activity from electrodes placed directly on the cortical surface. By bypassing the skull, these systems capture signals with far higher signal-to-noise and bandwidth than EEG, while still reflecting the activity of neural populations rather than individual neurons. Some arrays are designed for short-term use during surgery, others are implanted chronically and intended to remain in place for years. That split drives differences in materials, packaging, and regulatory pathways, and shapes what data can be accessed over time.

Clinically, ECoG has a clear role. Surface electrodes are standard tools for functional mapping and epilepsy monitoring, where identifying language areas or seizure foci directly informs surgical decisions. Given its clear utility, hospitals already greatly tolerate that invasiveness. More recently, interest has shifted toward ambulatory ECoG systems that extend recording beyond the hospital. These devices aim to capture brain activity during everyday life, not just short, controlled tasks.

A small group of companies illustrates how trade-offs are being productised. Precision Neuroscience frames its thin, high-resolution cortical arrays as temporary implants, soon integrated in real clinical workflows through a partnership with Medtronic. NeuroPace occupies the chronic end of the spectrum, with an implanted epilepsy interface that generates long-term ECoG recordings. NeuroOne focuses on thin-film electrode platforms as enabling technology for diagnostic and therapeutic use, while CorTec demonstrates that surface interfaces do not have to be short-lived, building chronic, bidirectional systems that challenge the assumption that higher-fidelity surface recording is inherently temporary.

Intracortical interfaces go all the way in, using penetrating electrodes to record activity from neuronal populations within the cortex. These systems are often described in terms of spikes and local field potentials, and they offer the highest spatial resolution and information throughput of any brain interface. That fidelity comes at a cost. Once electrodes cross the brain surface, biology becomes the dominant constraint. Tissue reacts, electrodes shift, and encapsulation gradually changes what can be recorded. Maintaining stable signals over years, not weeks, is as much a materials and packaging problem as a decoding one.

Most intracortical arrays fall into a familiar set of uses. Users learn to control cursors, select icons, type text, or manipulate assistive devices through decoded motor intent. More recently, speech decoding has emerged as a viable application, translating neural activity associated with attempted speech into text. It is important to be precise about what is being read. These systems decode intended movements or speech motor plans under constrained conditions, not free-form thoughts or memories. Progress is heating up, but unfolds through small clinical trials, careful endpoint selection, and repeated iteration.

The companies in the invasive space reflect different approaches on how to manage that complexity. Neuralink pairs flexible threads with a custom surgical robot and a potential consumer-facing narrative, while advancing through early human trials. Blackrock Neurotech represents a more established backbone of the field, with the Utah Array and NeuroPort system underpinning decades of intracortical research. Paradromics is pushing toward very high channel counts with a speech-first clinical focus, while BrainGate does not function as a product company and can be seen as a research institute.

Not all brain interfaces read electrical signals. A growing class of systems infers brain state indirectly, using proxy signals that are physiologically or behaviourally coupled to neural activity. Eye tracking and pupil-linked responses are a good example. They don’t measure brain waves, but pupil dilation and gaze dynamics are tightly linked to attention, arousal, and decision processes, which is why they sit at the core of modern XR interaction stacks.

Optical methods like fNIRS take a different route, tracking haemodynamic changes associated with neural activity and linked to states like focus and cognitive load. To that list, you can add a growing list of body-level signals that reflect central control loops and read consequences of brain activity rather than the activity itself. New modalities, like ultrasound-based armbands that decode hand and wrist motion, are entering the field, offering intent sensing without electrodes.

In practice, these modalities tend to work better for state estimation than for fine-grained control. Fatigue, stress, workload, and vigilance are easier to infer than precise intent, which is why many products gravitate toward dashboards and scores rather than command interfaces. When interaction is required, robustness usually comes from combining multiple readings. For example, gaze narrow options, micro-gestures confirm, while voice can clarify. Individually, these signals are noisy and limited, but stacked together, they increasingly support usable interaction. Yet, interpretation remains risky. Proxy signals are informative, but they support much more narrow claims. They can increasingly indicate changes in state, but are far from explaining causes or reveal what a user is thinking.

The neurotech landscape reflects that pragmatism. Meta has leaned heavily into multimodal interaction, combining eye tracking, hand input, voice, and wrist-based sensing in its Orion and XR work. Dedicated eye-tracking players like Tobii and Pupil Labs focus on the attention and gaze side of the spectrum. On the optical front, Mendi, Kernel, Gowerlabs, and Artinis illustrate how fNIRS is being positioned for research and applied monitoring. And at the state-decoding end, consumer wearables from Empatica, Oura, and WHOOP show how far you can go by reading the body as a proxy for the brain, without claiming direct access to neural signals.

Note: This list is intended to be informative, not exhaustive. The current neurotech landscape includes a long range of modalities. Some important techniques, like endovascular BCIs, are not discussed. To explore more, check out the startups in the Neurofounder Startup Map.

(Cover image credit: Mendi [L] & Pupil Labs [R])