At first, there was the space race. Then came a scramble for AI. Now billionaires are flocking to the neurotech arena. Increasingly, ultra-rich investors are taking stakes in brain-computer interface startups. The concept of reading the mind and connecting it to the outside world was long thought impossible. But now that the question is no longer if it will reach the market but when, tech moguls are looking to have their names attached to the first commercial devices.

The biggest personality in neurotech, at least to the general public, remains Elon Musk. The serial entrepreneur founded Neuralink in 2016, creating a frontrunner in the race to bring BCIs to patients and introducing the concept to many outside the field. But since Musk, several other eccentric billionaires have entered the space. In recent months, Mark Cuban invested in a budding startup, and Musk’s AI nemesis, Sam Altman, announced his own neurotech venture. Below, I map the key billionaires shaping the field, their investments, technical approaches, and what’s driving their bets.

The man who arguably got the party started. After making big money with the PayPal gang, building a car company, and sending rockets beyond the atmosphere, Elon Musk co-founded Neuralink. For many, Neuralink was their first introduction to “chips in the brain.” In its early years, Musk broadcast grand ambitions, imagining a future where everyone might live with a brain implant. That stirred plenty of controversy. But as the company has matured, and while Musk has been busy buying social media brands and venturing into politics, Neuralink is becoming a frontrunner for bringing the first intracortical brain-computer interfaces to the market.

Neuralink is currently building and testing two core technologies. The main product is the N1 intracortical BCI: a dense set of flexible micro-electrode threads that capture high-resolution signals from deep within the brain. To insert the device, Neuralink created the R1, a surgical robot designed specifically for the surgery. Together, the pair has strong potential for people who’ve lost agency due to stroke or spinal cord injury, capturing some of the most detailed signals achievable. However, competitors argue the approach is too invasive for broad applications. Even so, over the past two years, Neuralink has scaled from its first patient to more than 10 patients across three countries.

Musk was part of the founding team in 2016 as lead backer and public face. He’s appeared at product demos, investor talks, and major announcements, though he isn’t involved in day-to-day management. With an undisclosed investment and a renewed, futuristic mission to enhance human potential by bridging the brain and computers, Musk has propelled the company into the spotlight. He’s been loud, but he can also claim credit for backing the most talked-about brain-computer interface in the industry.

After falling out at OpenAI, Sam Altman and Musk entered a very public feud. The latest episode involves Altman announcing his own brain-computer interface company. Over the summer, he announced the founding of Merge Labs, a neurotech firm that will likely work closely with core AI technology developed at OpenAI. Little is known about its approach. Merge Labs may not directly compete with Neuralink, but Altman has already competed with Musk for media attention in the neurospace.

Merge Labs’ approach isn’t yet public, beyond some indications that it will pursue a minimally invasive BCI; the opposite of Neuralink’s invasive intracortical path. Altman has said non-invasive is the way to go, previously lauding read-only, non-surgical technologies. Mikhail Shapiro has reportedly been snapped up to lead the technical side of the team, a Caltech researcher with expertise in ultrasound and gene-modulated neural interfacing. It’s also fair to assume AI will play a large role. In theory, the diverging approach doesn’t preclude Altman from targeting the same patient group as Neuralink.

Altman is expected to take a chair role, leaving day-to-day management to a seasoned health-tech executive. Reports suggest links to OpenAI talent and know-how, and the company has reportedly raised $250m at an $850m valuation. Throwing money at the problem isn’t a sure path to success, but Merge Labs will be one to watch over the next two years.

While less of a personal endeavour, Mark Zuckerberg has also entered the neurotech arena. Through the acquisition of neural-interface startup CTRL-labs, he brought top talent and tech into Meta’s product stack. The deal reportedly cost up to $1 billion, making CTRL-labs one of the most valuable neurotech startups at the time. Unlike other billionaires treating neurotech as a side project or portfolio investment, Zuckerberg acquired an asset that could be directly integrated into Meta’s existing business.

CTRL-labs was founded in 2015 in New York City and acquired by Meta in 2019. Over the past six years, Meta has poured significant R&D into what is now Meta Reality Labs. Zuckerberg didn’t demand immediate output or profitability, similar to his approach with WhatsApp and Instagram. In recent months, Meta finally unveiled its first product from the work: an EMG neural wristband that lets users control Meta Ray-Ban smart glasses with subtle hand movements. While it offers no clinical value yet, Zuckerberg is the first billionaire to bring a consumer neuro-interface to market.

Zuckerberg began marching toward a metaverse vision years ago. While not everyone embraced the early demos, he now seems to be advancing VR/AR through more incremental, practical steps. The VR/AR glasses were the first real-world interface; they’re now complemented by more intuitive, intent-based input. Extend that trajectory and you can see where he wants to go: a Meta ecosystem where lightweight neural inputs make digital interaction feel natural, perhaps long before any “chip in the head” becomes mainstream.

Peter Thiel is increasingly viewed as a polarising investor. The former PayPal “mafia” colleague of Musk has used his capital to back Trump’s campaigns, several AI-based startups, aerospace firms, and defense technology. Adding to this list is neurotech: in 2021, Thiel invested in one of the field’s more established companies, Blackrock Neurotech, founded in 2008, participating in an undisclosed round rumored to be around $10 million.

Blackrock, based in Salt Lake City, Utah, is known for its implantable microelectrode arrays, the Utah Array (invented at the University of Utah). These high-channel devices enable high-resolution intracortical recording and stimulation. More than 40 people have received a Blackrock array, making it one of the most advanced players in the space. The arrays have been used in numerous research studies, and Blackrock positions itself primarily as a supplier of core interface technology rather than a direct end-user application company like Neuralink or Synchron.

The investment fits Thiel’s general portfolio approach. He routinely bets on frontier technologies across multiple sectors, including longevity, so backing a principal firm making neural interfaces a reality is no surprise. Thiel hasn’t said much publicly about the deal, keeping his presence in neurotech relatively low-key. This investment approach mirrors the company he backed: a BCI outfit soon quietly entering its third decade of building high-quality interfaces.

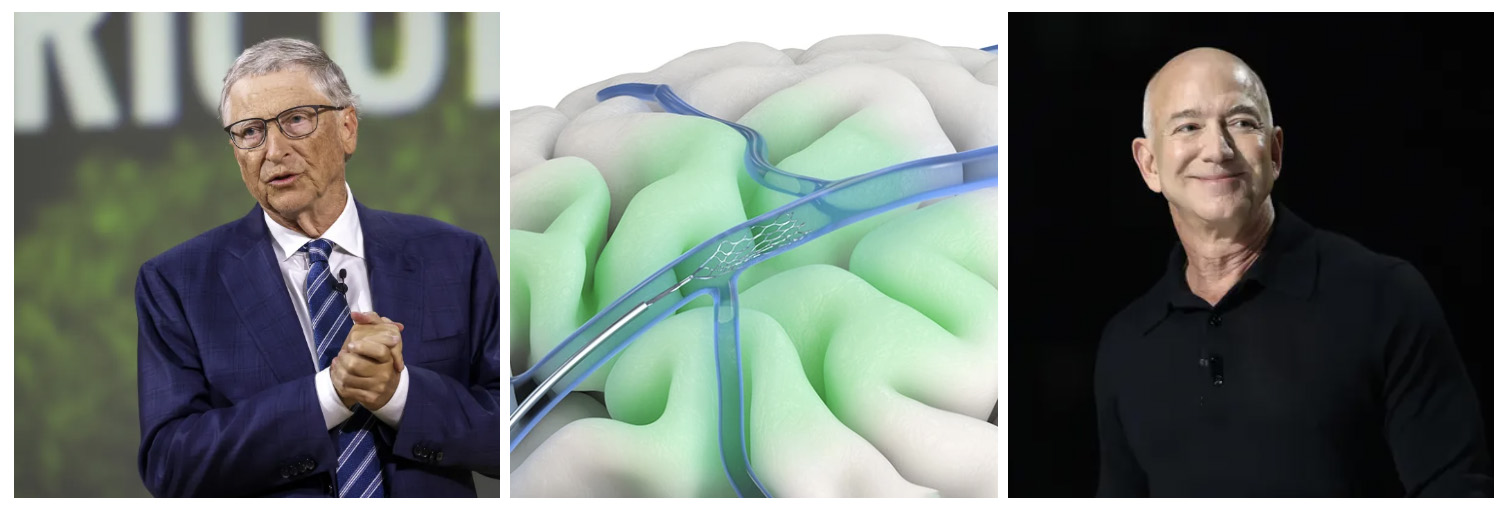

Two men who have both been called “the richest man on earth” have now invested in a principal BCI company. Each channelled Series C investments through personal vehicles, taking meaningful stakes in Synchron, one of the most important players in the field. Bezos and Gates have no operational roles, making this a far less ego-driven entry than some earlier examples. Yet if Synchron becomes one of the first to market, their names will surely be cited as key backers of a revolutionary neurotechnology.

Synchron was founded in 2016 and takes a different approach to brain-computer interfaces than most competitors. It is developing endovascular BCIs (“stentrodes”): stent-mounted electrode arrays delivered via the jugular vein into cortical veins near the motor cortex. This approach avoids open-brain surgery. The first U.S. human implants were performed in 2022, with recent demos showing BCI control of consumer devices, including Apple hardware.

Bezos and Gates both have unprecedented personal wealth to deploy into tomorrow’s technology. Gates, a prominent climate advocate, often backs technologies with clear societal value through his investment vehicles and philanthropy. Viewed through that lens, the Synchron investment makes sense: a minimally invasive pathway that is among the most clinically de-risked routes to brain-computer interfacing. Bezos often invests via his own firms, incorporating space and climate tech in Amazon-adjacent companies. But there’s no obvious Amazon “brain chip” on the horizon. Perhaps even Bezos knows that few people would sign up to have Jeff looking into their brains.

The latest billionaire entry is Shark Tank celebrity Mark Cuban. The man who judges investments for a living, and somehow still decided to trade Doncic to the Lakers, has joined his billionaire peers by investing in Synaptrix Labs. The amount is undisclosed, but with the company only just founded, Cuban likely plays a significant early role financially. Synaptrix is going fully non-invasive, building an EEG-based wearable to decode motor intent and enable device control.

The company is very new, and little is known beyond its focus on non-invasive EEG interfaces. EEG is seeing a resurgence in neurotech, especially on the consumer side. But also for some clinical use cases, where extreme signal detail isn’t required, it’s emerging as the simplest and most user-friendly option. Synaptrix aims to decode motor intent using EEG to support straightforward tasks, such as controlling mechanical wheelchairs.

For more info on Cuban’s recent investment, check out the Forbes article by the ever-resourceful Naveen Rao.

James Fickel, a crypto-made investor, has recently become a major backer of brain science, writing large checks into frontier outfits like Forest Neurotech and supporting brain-mapping efforts such as E11 Bio. His Amaranth Foundation frames the thesis as extending healthspan and building the toolkits that let us read and modulate the brain, putting him in the “infrastructure for neurotech” camp.

Fred Ehrsam, best known for Coinbase and Paradigm, has drifted from crypto rails to neural I/O. He’s backed hardware projects like wrist-based EMG control and has reportedly incubated Nudge, a non-invasive brain-health bet staffed with ex-BCI talent, positioning him as both financier and founder in the space.

Reid Hoffman, co-founder of everyone's favorite social media, LinkedIn, is leaning into non- or minimally invasive approaches, pairing AI with ultrasound and other gentler modalities. His recent bets include early funding for teams building wearable or helmet-style systems aimed first at therapeutic access rather than enhancement.

What started with one slightly lunatic-sounding billionaire launching a “chip-in-the-brain” firm has sparked a long list of wealthy benefactors putting their money into neurotech. While this article takes a more light-hearted view of that trend, there are more ways to look at it.

On one hand, having individuals with vast resources, but not always deep domain knowledge or the right intentions, leading the charge toward clinically approved neurotech can be risky. People like Zuckerberg, Musk, Thiel, and Altman are never far from controversy, and much of that criticism is justified. Should something as sensitive as technology that interfaces directly with our thoughts really be steered by tech billionaires? What happens if they cut corners, play fast and loose, or pursue ulterior motives?

On the other hand, money is money, no matter whose hands it comes from. Science is increasingly underfunded, and many of these technologies will serve relatively small patient populations. Neurotech carries extremely high development costs and long approval cycles. Weathering that gauntlet of years with little revenue and limited visibility into future income often requires deep-pocketed backers. If neurotech’s “cool factor” attracts capital that might otherwise overlook these problems, that may be a net positive and something to be happy about.

Ultimately, it’s up to the reader to decide how to view these developments. What’s clear is that neurotech is heating up, and these billionaires are pouring oil on the fire. 2026 looks poised to be a pivotal year; let’s see which headlines the billionaires make next.