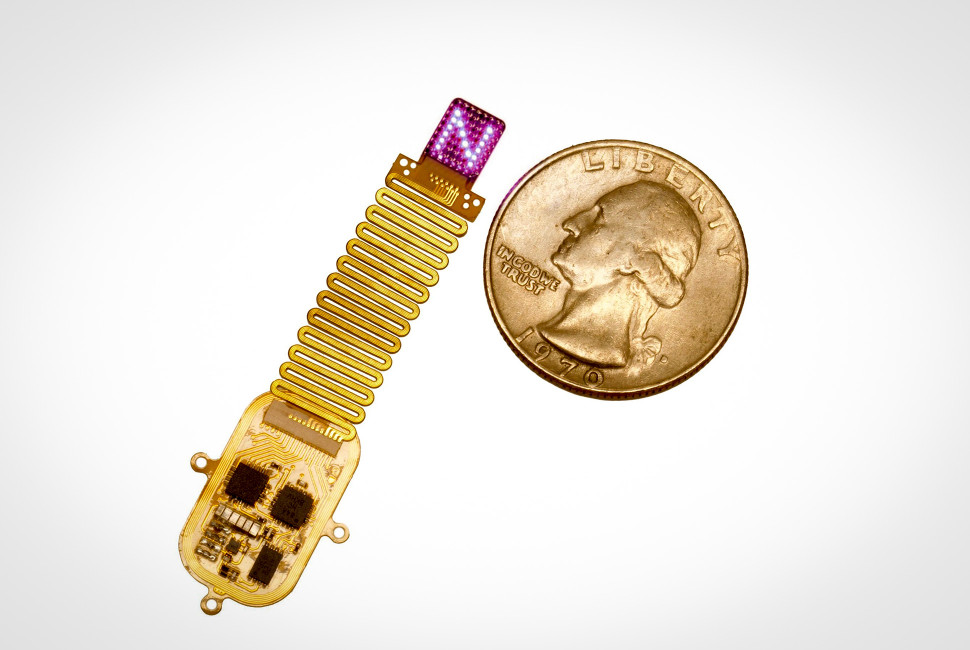

A new implant, produced by Northwestern University researchers, uses light to deliver information directly into the cortex. The device sits under the scalp, on top of the skull, and wirelessly drives a programmable array of up to 64 micro-LEDs, allowing researchers to project light patterns through bone and into brain tissue. In Nature Neuroscience, the researchers show how mice with light-sensitive neurons learned to interpret different spatiotemporal patterns as meaningful cues, using those inputs to guide decisions without relying on touch, sight, or sound.

Optogenetics pairs gene delivery with light to control specific neural populations with high precision, but that precision has been hard to carry outside tightly controlled lab settings. The clearest commercial progress has concentrated in retinal disease, where delivery is localized and vision outcomes can be measured directly. Cortical applications remain in its infancy. Northwestern’s new implant pushes the device side of the equation forward by delivering stimulation through the skull in a compact, wireless form, tightening the gap between optogenetics as an experimental tool and optogenetics as a usable input channel.

Northwestern’s new implant builds on decades of optogenetics progress, and is engineered to deliver stimulation without the usual external light hardware and cables. The device is thin and flexible, designed to sit under the scalp on top of the skull. From there, it wirelessly powers and controls a programmable array of up to 64 micro-LEDs, each addressable in real time. The research team used red light and near-field communication (NFC) to keep the system battery-free, while still allowing precise timing and pattern control.

Instead of lighting up one point in tissue, the array can spread stimulation across multiple locations and sequence it over time. Many optogenetics experiments still rely on single-site activation, which is ideal for probing circuits but limited as an input channel. At Northwestern, the stimulation can be patterned, producing multi-point spatiotemporal “signatures” that resemble a low-resolution projection across cortex. The authors connect this to how sensation is normally represented, with perception arising from distributed activity patterns rather than isolated hotspots.

Those patterns are not just visible in recordings. In behavioral experiments, mice, genetically engineered to express light-sensitive ion channels in targeted neurons, were trained to associate specific patterns with task cues and rewards. Over time, the animals learned to discriminate between light patterns and act on them reliably, treating the stimulation as an input that could guide decisions. The study follows a standard optogenetics animal model, using mice engineered to express light-sensitive proteins, and does not focus on or claim a direct path to human use.

Most brain interfaces today are built to read. They record neural activity and use it to decode intent, while the stimulation side is usually secondary and delivered through electrical pulses that spread beyond the intended target. Northwestern’s system puts the emphasis on input instead: it delivers patterned signals into cortex with enough spatial control to act like a low-bandwidth write channel. That is why, in theory, it maps naturally onto future use cases where feedback matters, such as giving prosthetic users a more informative sense of touch or delivering structured cues during rehabilitation.

However, the practical limitation is that optogenetic stimulation depends on more than a device. The experiments rely on neurons that have been made light-sensitive through gene delivery, and the study does not address how that biological step would be achieved safely and durably in people. In the near term, the device is most valuable as research infrastructure, because it makes it easier to test precise, repeatable stimulation patterns, including closed-loop experiments that adjust input based on behavior or recorded activity, without being confined to single-site activation.

Optogenetics becomes product-like when three parts work together. The first is biology: the light-sensitive proteins have to reach the right cells, stay there, and keep working over time. The second is light delivery: how efficiently light reaches the target cells, how much heat is generated, and whether power and packaging can support long-term use. The third is information: whether stimulation can be structured into signals that carry meaning, and whether those signals can be tested and refined in closed-loop settings. Northwestern’s implant advances the light and information layers by delivering patterned, multi-point stimulation wirelessly, while leaving the gene-delivery requirement unchanged.

That light-delivery problem is being pushed with increasing engineering discipline. Instead of custom-built lab setups, optical stimulation hardware is starting to look more like a platform. Groups are building integrated systems that can deliver many points of light with repeatable timing and intensity, closer to an addressable array than a single light source. That includes OLED-on-CMOS approaches that offer pixel-level control, and implantable micro-LED arrays designed for long-term use on the cortical surface.

Retinal disease has become the first commercial avenue for optogenetics, largely because delivery is localized and vision outcomes can be measured directly. Several companies are using gene therapy to make surviving retinal cells light-sensitive and then testing whether patients regain usable visual function. Nanoscope, GenSight, and Ray Therapeutics have reported clinical progress in this direction, while Science Corporation is developing an optogenetic gene-therapy and microLED-based system aimed at the same category. Larger pharma has also previously moved into the space through acquisitions of optogenetics-based retinal gene-therapy assets.

Outside vision, hearing is one of the few areas where an optogenetic path is clearly defined. The goal is to engineer an optical cochlear implant that can stimulate the auditory nerve with finer frequency resolution than today’s electrical systems, which often spread current and blur pitch information. Some startups are starting to build toward that concept, while academic work continues to test whether light-based stimulation can deliver tighter, more selective activation patterns inside the cochlea.

In parallel, the light-sensitive proteins themselves are being tuned to work at lower light levels, including variants aimed at responding under everyday indoor lighting. Higher sensitivity reduces the power needed at the device, which in turn reduces heat, bulk, and the amount of hardware required to deliver usable stimulation. Cortical uses are still at an earlier stage because they demand everything at once: broad, durable gene delivery, stable long-term function, and an implant that can run for extended periods without adding complexity for patients. Northwestern helps clear much of the device hurdle, but the biology still decides how far and how fast optogenetics can go.

[Cover image credit: Mingzheng Wu/Rogers Research Group]