Independent researchers from Osaka and Kyoto universities have published a long-horizon, open dataset of chronic electrocorticography (ECoG) recordings using CorTec’s Brain Interchange ONE system. The dataset, published in Nature, contains recordings from two implanted nonhuman primates, spans multiple task paradigms, and covers over 500 days of use. Long-term implanted datasets of this kind remain rare, particularly from fully wireless systems operating over extended periods.

As the brain-computer interface field matures, questions around durability increasingly shape how systems are evaluated. Many platforms have demonstrated stable recordings across sessions, an increasing amount now also in humans, but far fewer companies have shown how performance, maintenance burden, and reliability hold up over extended periods. Longevity, in that sense, has become one of the central constraints standing in the way of wide-spread BCI adoption.

Longevity is one of the least visible constraints in neural interfaces, yet it often determines whether a system can move beyond controlled trials into sustained use. In practice, longevity is not a single property. It spans material stability, whether the device and its packaging remain intact over time, interface stability, whether electrode contact remains reliable, signal stability, whether recorded features remain interpretable across sessions, and use stability, whether the system remains usable without escalating calibration, downtime, or maintenance burden. These layers are frequently conflated, even though progress in one does not automatically translate to the others.

For Frank Desiere, CEO of CorTec, what ultimately matters most is not whether an implant survives structurally, but whether it continues to function as intended. “The most critical aspect is functional stability, meaning the signal quality remains consistent enough that decoding algorithms don’t need constant retraining,” he says. In his view, longevity is frequently reduced to material survival alone. “A device can remain physically intact while the signal degrades due to the body’s immune response. True longevity means the interface remains transparent and reliable over years, not just days.”

Where systems fail over time depends strongly on how invasive the interface is. In penetrating and endovascular approaches, biological responses can gradually reshape the recording environment through tissue reactions and micromotion. In less invasive modalities such as ECoG, those biological effects tend to be more constrained, shifting the long-term challenge toward other sources of failure, as Desiere notes.

“For approaches like ours, the brain-electrode interface is actually the more solvable problem. The biology is surprisingly cooperative because we don’t penetrate the tissue.” Desiere says. “The real challenge is the boring engineering reality. Protecting electronics, connectors, and cables from the harsh, salty, and mechanically active environment of the human body for a decade requires absolute perfection in encapsulation and manufacturing.”

In Scientific Data, part of the Nature Portfolio, a Japanese research team published a longitudinal wireless ECoG dataset recorded using CorTec’s Brain Interchange ONE system. Beyond it being a valuable ECoG dataset, the dataset stands out for its combination of duration, full implantation, and open access. Long-horizon implanted datasets of this kind are still uncommon, particularly when released in a format intended for reuse rather than internal validation.

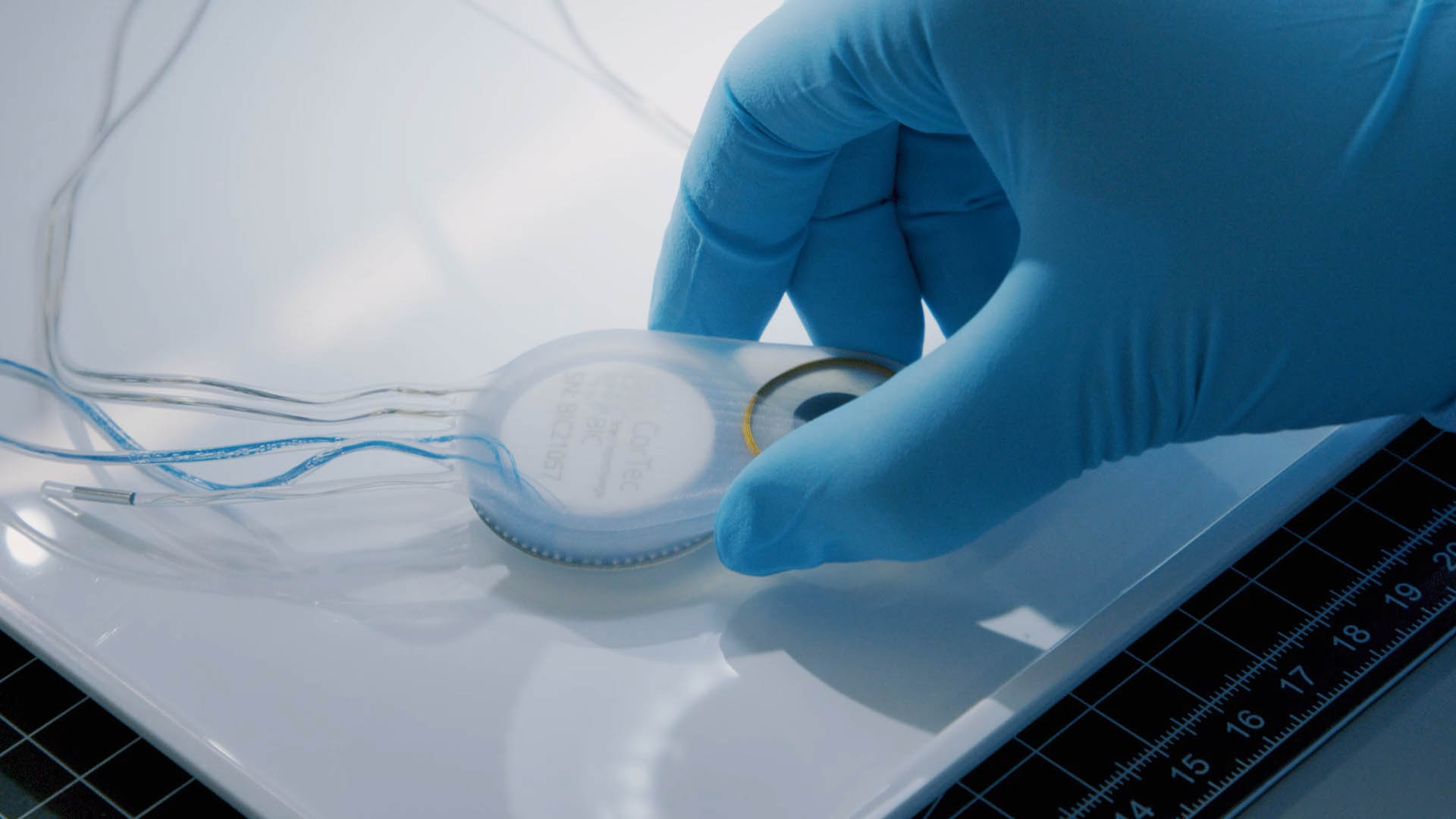

The dataset comes from two adult Japanese macaques implanted with CorTec’s wireless ECoG system. Subdural electrode arrays were placed on both hemispheres and connected to an implanted electronics unit that transmitted data wirelessly. Recordings were collected repeatedly over postoperative days across a range of conditions, including resting state, auditory tasks, voluntary movements, and somatosensory stimulation. Rather than presenting isolated snapshots, the dataset is structured session by session, reflecting how signals evolve over time.

From a longevity perspective, the paper focuses mostly on technical indicators. The authors tracked electrode impedance and examined resting-state and task-evoked activity across the recording period. Impedance values remained stable and within an acceptable range throughout, supporting the interpretation that the electrode-tissue interface did not show obvious degradation over hundreds of days in this configuration.

Frank Desiere is clear about how to interpret that result. “This dataset fundamentally de-risks the biological interface,” he says. “It proves that the brain tolerates the implant well and that high-fidelity signals can be maintained without the degradation often seen in penetrating arrays.” At the same time, he draws a firm boundary around what remains unresolved. “What it doesn’t fully address yet is the lifetime engineering reliability of the total active system, especially the ultra-long-term performance of hermetic packaging over a ten to twenty year horizon.”

The open release matters because it makes longevity something that can be examined, not just claimed. Public wireless ECoG datasets at this timescale remain rare, and many existing longitudinal datasets are difficult to reuse across groups due to inconsistent structure or limited metadata. By providing long-horizon recordings in a standardized format, the release lowers the barrier to studying stability, drift, and analysis choices using shared data. It turns questions that are often debated informally into questions that can be tested.

That shift reflects a broader change across the BCI field. Early human demonstrations and short-term results are no longer the only markers of progress. As well-funded BCI startups move through early clinical use and toward commercialization, attention is increasingly focused on what happens after the first months. Questions around signal stability, maintenance burden, system reliability, and replacement cycles are becoming central. In that context, independent, long-horizon evidence plays a different role than early trials. It does not replace clinical validation, but it helps clarify which interface approaches show credible longevity potential, offering the most value to prospective patients.