Apple’s acquisition of Q.ai was unusually large by Apple standards, reported at $1.6-$2 billion and widely described as its second-largest deal after Beats. That money is likely going towards improving how devices handle speech in messy, real-world conditions, including whispered or near-silent interaction. But acquiring Q.ai also opens a neuro-adjacent door; one involving reading intent from the body to decode signals that originate deep in the brain.

Q.ai is an Israeli startup of around 100 people. Known for audio decoding, their patent trail also covers optical sensing of facial micromovements and “non-verbal speech,” with claims extending into physiology and affect-related measurements. That combination opens two doors for Apple. One regards a new input modality: silent device control that serves accessibility needs and everyday privacy-first interactions. The other is more speculative: using peripheral signals as proxies for measuring cognitive and affective state, and deciding where, if anywhere, that belongs inside products like AirPods, iPhones, and Vision Pros.

Speech is usually treated as a string of coordinated sound. Silent speech interfaces treat speech as a motor act first, and only secondarily as an audio signal. Instead of listening to the voice, they infer intended words from the physical processes that produce it. In research context, that has meant applying EMG on the face or throat, ultrasound to the tongue, developing radar-like readings, and experimenting with camera-based lipreading, sometimes fused together into multimodal systems.

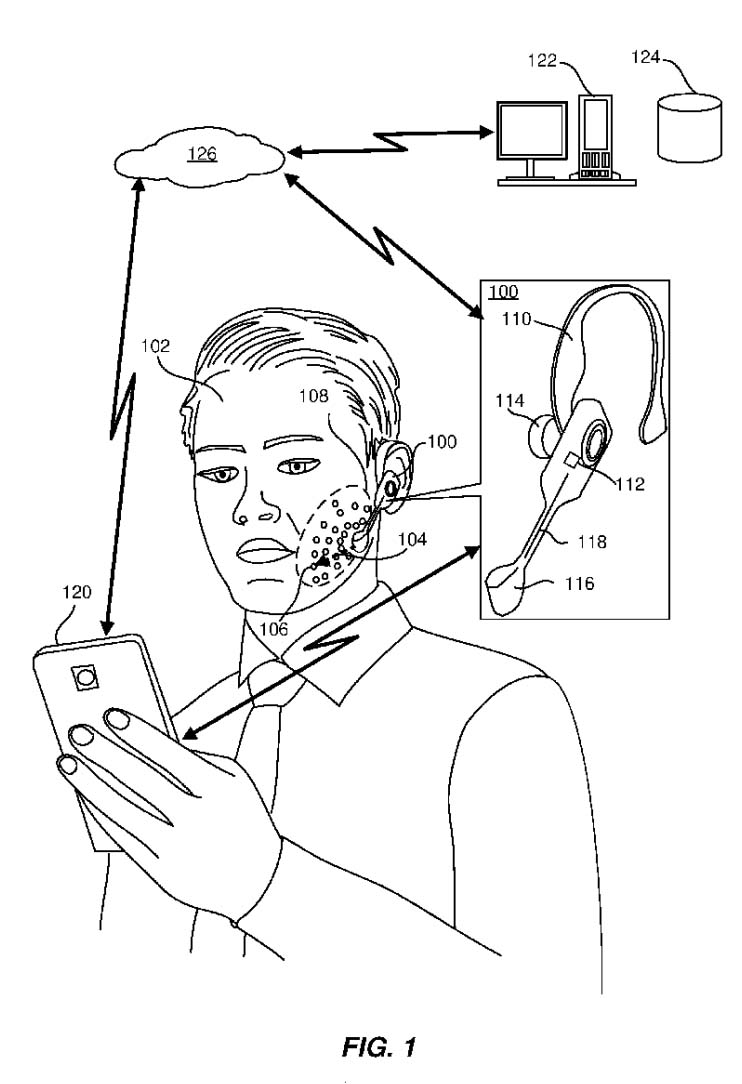

Q.ai’s patent filings describe an optical version of such an interface. In WO2024018400 and related U.S. filings, the system is framed as a head-worn wearable that projects coherent light onto selected facial regions, captures the reflected light, and analyzes subtle temporal changes in the resulting speckle patterns to determine micromovements. The claims go further than generic lipreading, specifying sensitivity to micromovements on the order of tens of microns and referencing muscle groups associated with articulation and even pre-vocalization recruitment. Using that stack, the system can read mouthed commands and whispered speech, and in some cases begin interpreting content before it is fully vocalized.

The accessibility upside of this technology is clear. A silent channel turns speech from something you must project audibly into something you can express through articulation alone, supporting people with reduced vocal volume, atypical speech, and enabling speech input in environments where voice control breaks down. It extends Apple’s existing accessibility stack without requiring a visibly different device.

Micromovement control still depends on usable facial musculature. It is an alternative motor pathway, not a motor-free one. When even that pathway is unavailable, Apple’s Switch Control support for brain-computer interfaces represents a different category that bypasses peripheral movement entirely. That avenue has already been explored in integrations with systems like Synchron's endovascular implant.

For most users, the silent speech appeal is privacy rather than accessibility. Vision Pro already formalizes eyes, hands, and voice as primary inputs. A silent speech layer would extend voice-like interaction into spaces where speaking feels awkward or exposed, without forcing users back to a handheld device. That ambition rings a bell: Meta is working on wrist-based EMG to capture subtle, private hand and finger signals for AR glasses control, treating the body as a low-friction input surface. In that context, frictionless body-based intent capture becomes a practical, privacy-first complement to voice, rather than a replacement for it.

The more ambitious part of Q.ai’s patent footprint goes beyond decoding speech. In WO2024018400A2, the system is described as determining not only non-verbal words and identity, but also emotional state, heart rate, and respiration rate from the same optical micromovement signals. The architecture sketches separate interpretation modules for these outputs, and even references photoplethysmography-like optical principles for deriving cardiac rhythms. In that framing, the face becomes a sensing surface for downstream physiological and affective proxies, inferred from motor and microvascular dynamics.

Cognitive and affective states modulate motor preparation, facial tension, breathing patterns, and micro-vascular changes. An optical system that projects light, measures reflections, and tracks micromovement dynamics can then model those changes. Research shows that contactless heart rate and respiration estimation from optical signals is feasible. However, performance varies sharply with motion, lighting, and individual differences. Translating that into stable “emotion” labels is harder still, because physiological proxies are sensitive to context and easily confounded by activity, stress, fatigue, and health.

In Apple’s product ecosystem, state recognition could be integrated across products . On Vision Pro, signs of fatigue or overload could mean fewer notifications, slower pop-ups, or a softer transition between immersive scenes. On AirPods, micromovement and breathing cues could help decide when to turn on translation, adjust noise control, or surface Siri. On iPhone, the impact would likely be very subtle, making “assistant without voice” interactions more reliable in noisy or shared environments but likely not presenting visible mood or stress scores.

At its core, Q.ai’s patent trail describes an interface layer that reads the body as a bridge to decoding intent and state. It does not measure the brain directly, as would be possible with Apple’s EEG Airpods patent. But it narrows the distance between neural activity and device behavior to the point that we could soon see more neuro-adjacent features in Apple’s products.