In a landmark for vision restoration, the PRIMA BCI retinal implant has enabled people with advanced macular degeneration (AMD) to recognize faces, read books, and even complete crossword puzzles again. Developed by Science Corporation, based on research originating at Stanford, the study was published in The New England Journal of Medicine, marking one of the first clinically verified demonstrations of functional vision restoration thanks to BCI.

Until now, treatment for AMD has primarily sought to slow disease progression, rather than restoring lost vision. The PRIMA system redefines that paradigm. By combining a sub-retinal photovoltaic chip with AI-assisted smart glasses, it restores “form vision” in patients with previously irreversible central blindness. The reported clinical efficacy benefits outweighed the risks, judged by the Data Safety Monitoring Board for European market approval, paving the way to revolutionize the treatment of vision restoration.

Five million people worldwide suffer from Geographic atrophy (GA), the advanced atrophic stage of AMD. It is marked by the loss of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells in the retina, the “camera sensor” of the eye that helps us differentiate the world. Once these cells die, visual signals can no longer reach the brain’s processing centers, leading to irreversible central blindness.

California-based Science Corporation acquired the assets to the PRIMA system, developed by the French startup Pixium Vision last April 2024. Science Corp is a neurotech company that creates components, such as software, hardware and probes specifically for neural engineering, offers Foundry services to other neurotech startups, as well as launching its own research into biohybrid interfaces and now PRIMA.

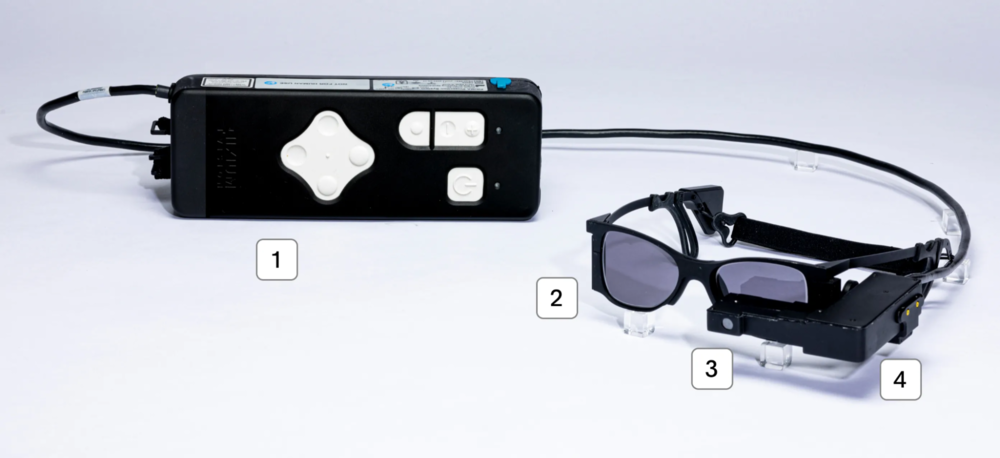

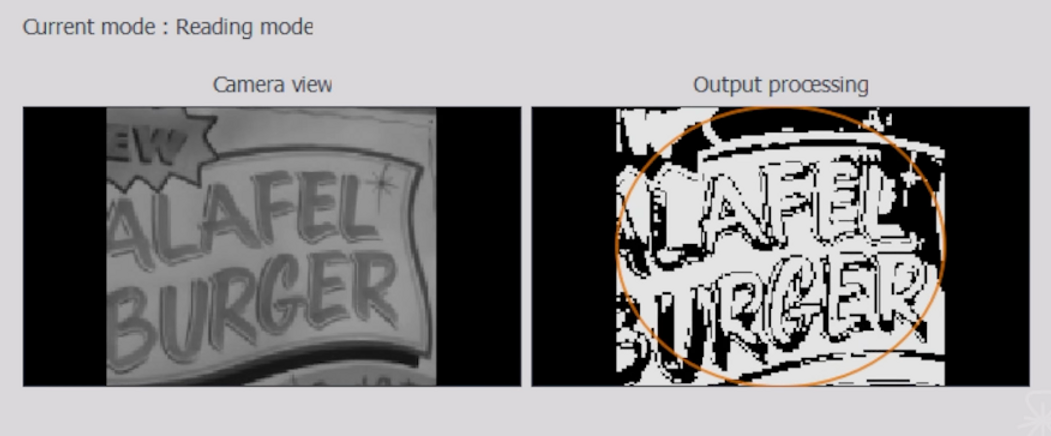

Roughly the size of a sesame seed, the PRIMA implant is a wireless 2x2mm photovoltaic chip containing 378 electrodes. It is inserted beneath the retina, where it converts projected near-infrared light into electrical stimulation. Specialized glasses equipped with a camera capture real-world images, preprocess them through onboard AI-enhanced software, and project them via near-infrared light onto the implant.

The resulting signals travel through the optic nerve to the brain’s visual cortex, effectively bypassing the degenerated photoreceptors. A handheld controller lets users adjust brightness or magnify text for specific tasks such as reading.

The multicenter clinical trial spanned five countries and enrolled 38 patients with geographic atrophy, 32 of whom completed the 12-month study. Participants underwent extensive visual rehabilitation to learn to interpret the prosthetic input. On average, they could read five additional lines on the standard eye chart, roughly a threefold improvement in visual acuity. Functionally, 27 of 32 patients (84%) reported using the device at home for letter and word recognition, reading, or identifying household objects previously invisible to them.

Importantly, this trial appears to mark a first: restoring “form vision”, perceiving structures, shapes, letters and words, rather than mere light flashes (phosphenes) achieved by earlier implants. Both the clinical coordinator, Professor Frank Holz (University of Bonn), and CEO Max Hodak of Science Corp emphasised that this is the first time fluent reading has been definitively shown in blind patients via “form vision” in the retinal prosthesis.

While the results are promising, there is still much work to be done to improve the nature of the vision experienced. Patients currently described the restored vision as monochromatic or low-colour, sometimes with a yellowish tint and lower dynamic range.

Interpreting these signals requires weeks of rehabilitation, as the brain learns to integrate the new visual input, a process researchers attribute to neuroplastic adaptation.

Researchers have their sights set on improving vision, face recognition and image clarity through efforts to incorporate computer vision and machine learning techniques in the PRIMA system.

Nevertheless, the results are transformative. The artificial vision is functionally sufficient for patients to read, recognize faces and re-engage in everyday activities once thought permanently lost. The evidence for independent home use represents a major inflexion point in vision-restoration devices.

Science Corp’s achievement sits at the intersection of several booming trends: the rise of BCIs, advanced implantable medical devices, and sensory-restoration technologies. In the vision space, many prior approaches focused on slowing degeneration (in AMD or GA) rather than truly restoring lost photoreceptor function.

The PRIMA System bypasses the degenerated cells, directly stimulating the remaining retinal cells via the implant and smart-glasses system. This shift is emblematic of a broader move from “neuro-preservation” to “neuro-restoration.” Moreover, these results signal a trend of the gradual adoption of implantable technology.

In the BCI ecosystem, this kind of high-impact outcome (real functional vision restoration) bolsters investor and regulatory confidence in neural-interface technologies. Given the ageing global population and rising incidence of AMD/GA, a successful rollout could trigger considerable market opportunity and spur competitors. It also underscores the importance of rehabilitation infrastructure, patient training, and integrated device-software ecosystems - just as we’re seeing in other neurotech segments (e.g., motor prosthetics, auditory implants).

The PRIMA System trial results announced by Science Corp break new ground: not merely slowing vision loss, but restoring meaningful central vision in patients previously deemed untreatable. Science Corp submitted regulatory applications for both the US and European markets, launched a patient registry last month, showing promising signs towards commercialisation.

While it remains to be seen how broadly and rapidly this technology will be accessible, the implications are profound for patients, ophthalmologists, device manufacturers and the evolving BCI industry. As regulatory pathways progress and real-world data accumulate, this development may mark the start of a new chapter in sensory restoration, one in which blindness due to advanced GA is no longer without recourse.