Digital phenotyping is reshaping neurology, passively detecting early disease signals, stratifying patients into precise subgroups, and opening up possibilities for precision medicine. But its real-world promise depends on more than just collecting data. The true challenge lies in deciding which signals are worth capturing, grounding them in validated neuroscience, and making them actionable in the clinic.

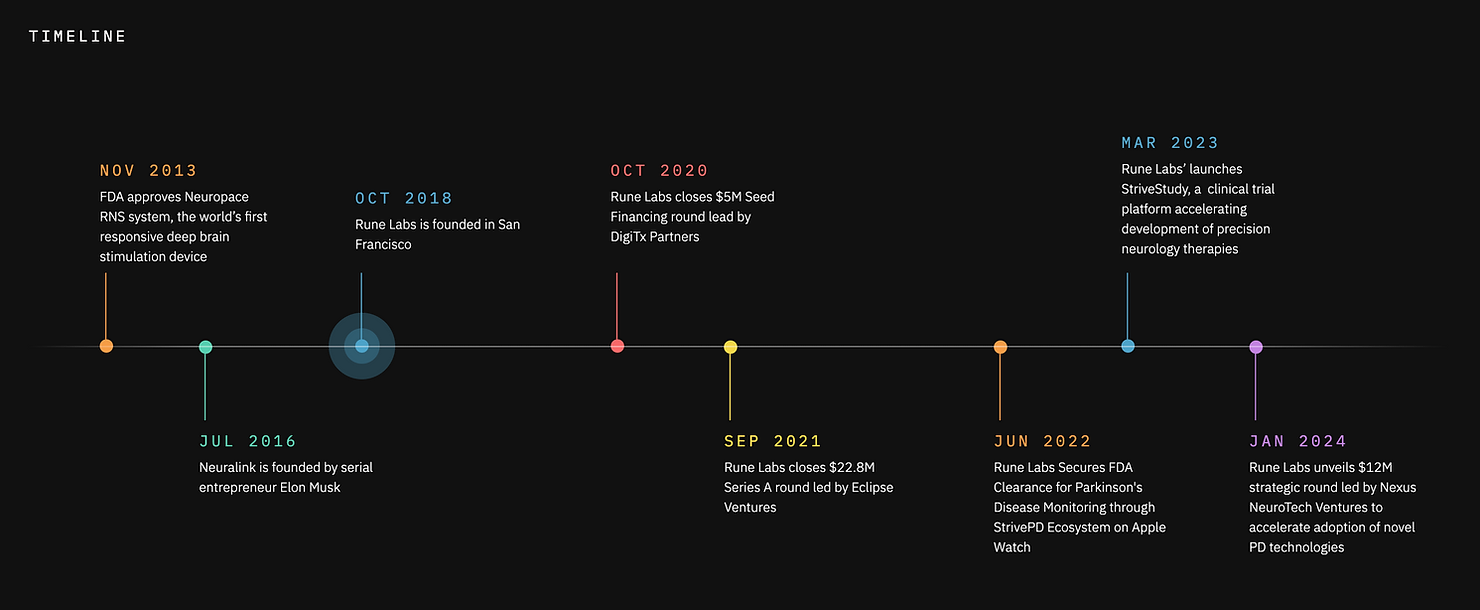

This is the space where Rune Labs has established itself as a leader. Founded in 2018, the company has built a precision neurology platform that integrates multimodal data collected from the Apple Watch (FDA-cleared for tremor and dyskinesia collection). patient-reported outcomes, and sensing-enabled deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices.

Its flagship product, StrivePD, supports people with Parkinson’s disease in tracking their symptoms and treatments, while at the same time providing clinicians with a richer picture of disease progression. For biopharma partners, the same platform accelerates biomarker discovery and therapy development, creating a unique bridge between everyday patient experiences and clinical research.

At the center of this work is Ro’ee Gilron, Lead Neuroscientist at Rune Labs, whose role spans both scientific rigor and translational impact. With a background in systems neuroscience and neuromodulation, Ro’ee helps guide how Rune Labs selects data streams, validates them against neuroscience frameworks, and translates them into insights that can genuinely shape care.

I spoke with Ro’ee about the principles behind digital phenotyping at Rune Labs, the trade-offs between signal quality and scale, and the “last mile” challenges of turning complex data into real-world clinical impact.

My main focus is helping patients get matched to the most effective approved therapies by learning from our large database of real-world treatment responses. Using the same data, we also support clinical trial partners in testing how well their therapies work and in guiding titration decisions for approved treatments. We do this through algorithm development on dense, time-series data that captures how symptoms and responses evolve over time.

A foundational principle for us is that there shouldn’t be a barrier between the kinds of data used in clinical research and the data used in real-world care. Historically, digital tools have focused on replicating clinic visits in a digital form, often relying on active tasks that require patient input. Those approaches are valuable, but they don’t scale easily and often fail to capture real-world behavior.

We prioritize passive measurement, leveraging the sensors people already use in daily life, like the accelerometers in their phones or the heart rate sensors in their watches. These provide incredibly rich, continuous data without additional patient burden. We also use a structured validation framework, or what we call our “V3” approach, that looks at technical accuracy, analytical reliability, and clinical validity. This ensures that the data we rely on is not just plentiful, but trustworthy and useful.

Balancing accuracy and scale is about understanding the minimum data needed to deliver value. For example, predicting fall risk doesn’t require second-by-second resolution; it requires enough data across thousands of walking events to see meaningful patterns. That mindset lets us harness the massive availability of real-world data without compromising on reliability.

Absolutely. One of the biggest challenges isn’t about the data itself but about how it’s integrated into clinical decision-making. Some clinicians may think they want to see data at its most granular, second-by-second or minute-by-minute, but in reality, that level of detail is overwhelming and not actionable in a busy clinic.

Our focus is on transforming those raw signals into summaries and insights that align with how clinicians make decisions. Even patients who are very data-savvy often realize they don’t need every datapoint; they need clear, synthesized information. The challenge isn’t collecting the data; it’s packaging it in a way that’s immediately useful in real-world care settings.

"The challenge isn't collecting the data; it's packaging it in a way that's immediately useful in real-world care settings."

We approach validation as a multi-step process. It starts with technical validation, confirming that a sensor is accurately measuring what it claims to measure. For instance, we verify that an accelerometer is truly capturing acceleration using external references and published data.

Next is analytical validation, where we test whether the algorithms interpreting those signals actually represent the behaviors in question. A good example is walking speed, which is tied to disease progression in Parkinson’s. We validate these models against in-clinic measurements and published standards to ensure they accurately reflect what they are purported to measure.

Finally, we do clinical validation, showing that the biomarkers correlate with clinically relevant outcomes. Our collaboration with Kaiser Permanente on fall risk is a good example: we demonstrated that passive gait metrics can classify patients into risk categories that align with real-world outcomes. That’s an example of the process we go through to ensure that our algorithms are “fit for purpose”.

One clear example is our work addressing the long-standing challenge of “motor diaries” in Parkinson’s disease. Many therapies were approved based on patients manually recording every 30 minutes whether they felt “on” or “off” medication: a subjective judgment of how well their treatment was working. These paper diaries are often filled out retrospectively and prone to error, yet they remain the regulatory gold standard.

Rather than viewing digital metrics and traditional diaries as competitors, we treat them as complementary. We use digital metrics to identify patients who are good at self-reporting and those who are not. If there’s a gap between the wearable data and the diary, that’s a signal we can use; maybe the patient needs training, or maybe the diary is unreliable for that individual. This approach helps improve trial sensitivity and reduce variability, ultimately shaping how therapies are assessed and approved.

The key is tailoring the same foundational data into outputs that meet the needs of different stakeholders. For patients, we focus on accessibility and building real-time trackers and easy-to-read reports that help patients see how their symptoms are changing and how medications are affecting them day to day. We also use large language models to summarize free-text journal entries, highlighting patterns like missed doses or symptom fluctuations.

For clinicians, the priority is efficiency. We distill complex data into concise reports that highlight actionable trends without overwhelming them. And for researchers, we provide deeper datasets and analyses that inform drug development decisions and health-economic outcomes. For example, whether a therapy reduces fall risk, or which has major implications for quality of life and healthcare costs.

The hardest challenge is integration into clinical workflows. Many neurologists are already overextended since there are only about 660 movement disorder specialists in the U.S., and they don’t have the bandwidth to manage another data portal. Even when they’re curious and forward-thinking, the tools need to fit seamlessly into their existing routines and clearly demonstrate value.

We’ve built tools like StrivePD and StrivePD Guardian that make this possible, but reaching critical mass among clinicians requires continued effort. The shift we’re aiming for is from a “push” model, where we’re trying to convince clinicians to use new tools, to a “pull” model, where they actively want them because they see the benefit for their patients and their practice.

I think we’re heading toward a future similar to what’s happened in diabetes care. Continuous glucose monitors started as decision-support tools and evolved into closed-loop systems that automatically deliver insulin. Neurology is on the cusp of a similar transformation.

For Parkinson’s, we’re already seeing continuous drug-delivery pumps and adaptive deep-brain stimulation devices that respond to brain signals in real time. As therapies become more complex, combining drugs, stimulation, and behavioral interventions, digital phenotyping may be critical for managing that complexity.

The future is a tightly integrated, data-driven ecosystem where patients are active participants in their care, and digital biomarkers help guide both clinical decisions and automated interventions.