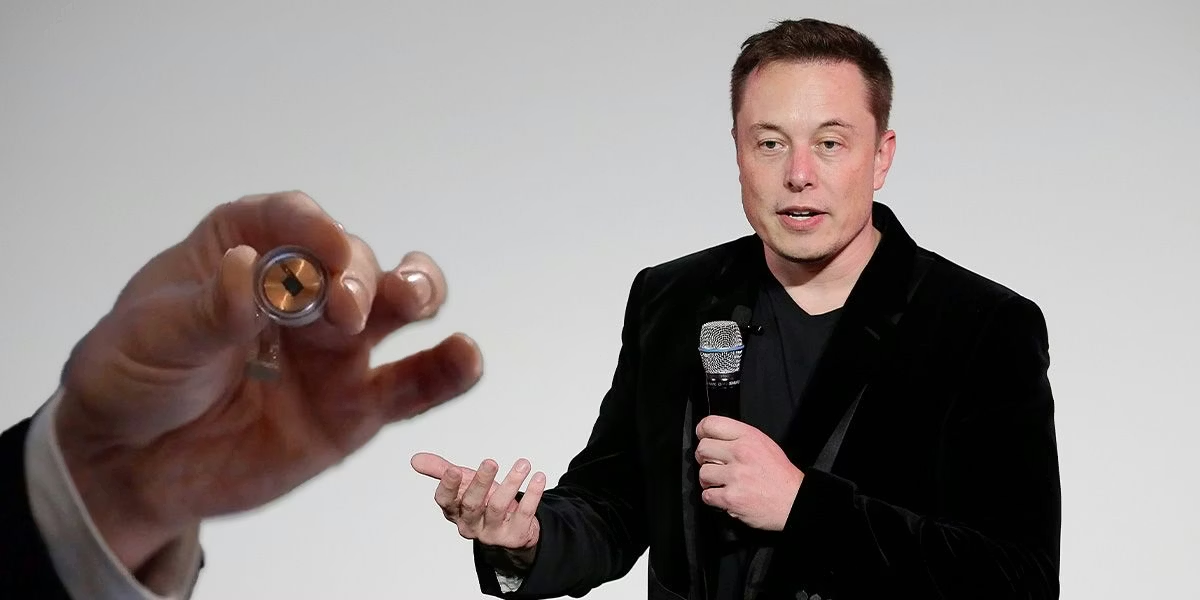

2026 has started with a bang, courtesy of the most explosive man in neurotech. Elon Musk declared on X that “Neuralink will start high-volume production of brain-computer interface devices and move to a streamlined, almost entirely automated surgical procedure in 2026.” He continues: “Device threads will go through the dura, without the need to remove it. This is a big deal.” But how big of a deal are Musk’s words in reality?

Neuralink is coming off a strong 2025. The company raised a $650 million Series E, extended trials to Canada and the UK, and reached an implanted base of around fifteen patients. This was achieved using Neuralink’s established approach, in which its surgical robot (R1) assists in inserting the implant (N1) into the cortex. Yet while the progress was significant and meaningful for patients living with severe paralysis, it still falls short of justifying Neuralink’s $9 billion valuation. That makes it worth asking whether Musk’s statement reflects a genuine projection of what lies ahead in 2026, or an inflated signal aimed at placating investors and markets.

Musk’s tweet is short, but it makes three claims at once: scale, automation, and a surgical breakthrough. Neuralink, Musk says, will move to “high-volume production” of its implants, supported by an “almost entirely automated” surgical procedure, where electrode threads are inserted through the dura without removing it. In a nutshell, Musk wants Neuralink to move to industrial deployment, to start generating return on investment. Yet can his ideas realistically map onto the current state of BCIs?

“High-volume production” is probably the most loaded statement in the tweet, because it implicitly shifts Neuralink from a clinical feasibility effort toward a scaling enterprise. In the context of invasive BCIs, "high volume" likely does not mean consumer-scale manufacturing, but rather a move toward devices designed for repeatable manufacturing, with stable yields and controlled quality. Even that step, however, sits somewhat awkwardly against the present clinical reality. Neuralink’s human deployment remains small, with just over a dozen implanted patients and a narrow focus on severe paralysis.

Automation is the second pillar of Musk’s claim, and arguably the more consequential one. “Almost entirely automated surgery” sounds radical, but in medical practice it rarely implies autonomy in the way the term might in robotics or manufacturing. More often, it means a robot-assisted procedure that remains clinician-supervised, with responsibility and judgment still resting on the surgical team.

Even so, automation matters because procedure throughput is one of the hardest constraints on scaling invasive neurotech. Operating room time, surgeon availability, training requirements, and outcome variability all cap how fast implants can be deployed. If Neuralink wants volume to be more than a narrative, reducing those constraints is unavoidable. This is also where the third claim in the tweet, about the dura, becomes central.

The dura detail is the most concrete technical sign Musk offers, and the reason he calls it “a big deal.” Inserting threads through the dura, the brain’s tough outer membrane, without removing it suggests a procedure with fewer steps and less tissue disruption, which could plausibly shorten surgery time and improve repeatability. For hospitals, keeping the dura intact can also mean simpler closure and potentially lower complication risk, both of which matter for adoption.

Moving away from removing the dura places Neuralink closer to a broader shift in invasive neurotech, where reducing surgical complexity and invasiveness for the patient have become central to a credible path toward scale. Companies such as Precision Neuroscience and Synchron are pioneering strategies around less disruptive access to the brain. Elon’s emphasis on passing through the dura, without removing it, mirrors that trend and suggests a possible adjustment in how Neuralink’s system is being prepared for real-world deployment.

Musk’s strategy follows a familiar pattern from his other companies. At Tesla and SpaceX, he has repeatedly taken products that were capital-intensive, slow to scale, and commercially fragile, and forced them onto a different trajectory by prioritizing throughput and automation. Once production and execution are standardized and tightly controlled, iteration accelerates, costs compress, and advantages compound. Musk seems to reason that the same logic can be extended into invasive neurotechnology.

Applied to BCIs, that logic implies that Neuralink will move more towards building a procedure platform rather than standalone devices. Scale, in this view, does not come from selling more implants, but from owning the entire delivery stack and reducing dependence on external institutions. This mirrors Musk’s broader tendency to internalize complexity rather than negotiate with it. The tension is that in medicine, speed does not only trade off against cost and quality. It also trades off against trust, governance, adverse-event tolerance, and institutional acceptance.

That tension becomes clearer when viewed through a financial lens. Investor materials reported by Reuters and Bloomberg outline internal targets that imply roughly $50,000 in revenue per implant and longer-term ambitions of 20,000 surgeries producing over $1 billion annually. Those figures are not unprecedented in implantable neurotechnology. But they only hold if reimbursement pathways mature, hospitals can deliver the procedure without eroding their own margins, and the intervention produces outcomes that clearly justify its cost.

That last condition is the most fundamental. An expensive, invasive cortical implant only becomes economically viable if it delivers functional improvements that are both clinically meaningful and durable for patients. For a subset of people with severe paralysis and advanced ALS, the trade-off between surgical risk and regained agency may strongly favor intervention. For others, especially as less invasive alternatives improve, the balance is less obvious. How many patients ultimately fall on the favorable side of that equation will determine the true size of the addressable market.

This is where broader skepticism around BCI economics comes into focus. Under current conditions, there is limited room for multiple invasive BCI approaches pursuing similar clinical goals. Either the market expands materially, or competition collapses toward a small number of players. Musk’s emphasis on scale and automation can therefore be interpreted in two ways: as a means of sustaining a valuation built on future expectations rather than current deployment, or as an attempt to secure the delivery layer early, so that when reimbursement and indications broaden, Neuralink is best positioned to serve patients at volume.

What Musk’s comments can realistically influence in 2026 sits somewhere between those two interpretations. He is unlikely to compress trial timelines, bypass regulatory pacing, or shortcut safety requirements. But he can influence how capital is deployed, whether clinics and delivery infrastructure are built alongside trials, and which partnerships are pursued. Just as importantly, his statements shape internal expectations, encouraging teams to operate as if scale is approaching. Only if that pressure results in shorter procedures, more sites, and gains in capacity, Musk’s infamous playbook may begin to intersect with medical reality.