The neurotechnology field has been chasing a “holy grail” interface for years: recording neural signals with the high-fidelity of invasive electrode arrays, but with the ease and low burden of noninvasive sensors like EEG. For a moment, “neural dust” appeared to be the answer. In reimagining the neural interface as a distributed scattering of tiny, microscale sensors throughout the brain, neural dust heralded brain-wide sensing and stimulation without bulky implants.

Early demonstrations in animals were striking, excitement roused in headlines. Yet, ten years later, neural dust is not in human trials, and the term itself has faded from the spotlight in neurotech discourse. So what happened? Neural dust didn’t disappear. Instead, as with any deep-tech frontier, it forked into multiple research lineages and embarked on the slow grind of science that can’t be brute-forced into human adoption, highlighting the arduous realities of neurotech evolution and translation.

Like most new technologies, nomenclature can get blurry as new iterations emerge. There’s not really a single name that encompasses the overall category of micro/nanoscale sensors sprinkled throughout the brain/body, using external fields to wirelessly power and communicate bidirectional signals outside the body. In this article, I’ll use ‘neural dust’.

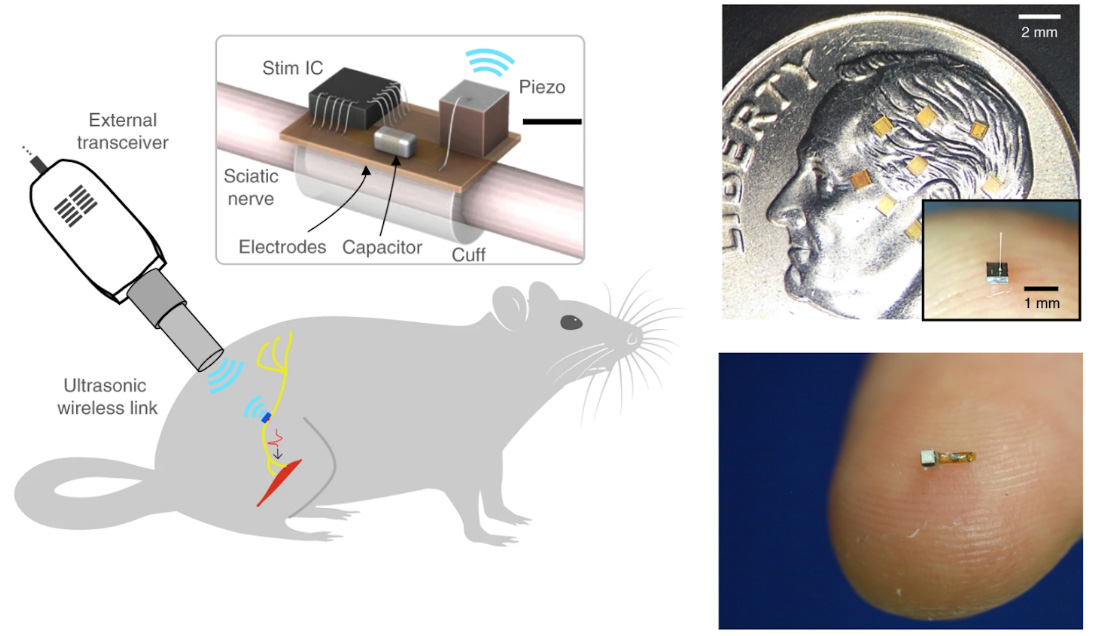

This term was coined ten years ago by researchers from Berkeley, lead by Michel Maharbiz and Jose Carmena, for their demonstration of tiny, wireless sensor dust ‘motes’ that could transmit peripheral nerve and muscle signals from inside rats. Over time, other teams inherited this core template - distributed sensors, remote power and remote readout - swapping technical choices in search of the most optimal neural interface.

Now, the “neural dust” concept has expanded to encompass ultrasound-powered micro-implants (e.g. “StimDust”) to wireless networks of microimplants (e.g. “neurograins”), injectable electronic nanoparticles (e.g. MENPs) and even tiny sensors fused to immune cells (e.g. “Circulatronics”). They differ substantially in implementation, but share the same intention: reduce the burden of “getting inside the brain” while keeping meaningful signal fidelity.

In the original Berkeley work, the key novelty was passive operation: the new dust-like implants avoided chunky batteries and/or wired leads of conventional BCIs. Instead, piezoelectric crystal ‘motes’ were powered by ultrasound. The ultrasound pulses hit the crystal motes, causing them to vibrate. Local neural activity modulates the mote’s electrical interface, altering the mote’s ultrasound echo (the ‘backscatter’), which the external unit decodes. Imagine thousands of motes distributed across the brain. These systems have generally demonstrated meaningful neural signals, but not yet dense, stable single-unit recording at scale.

After demonstrating neural recording capabilities, it was natural that researchers turned to stimulation. The Berkeley team introduced “StimDust”, leveraging ultrasonic power. Meanwhile Brown University’s Nurmikko led the “Neurograins” efforts, which uses radiofrequency as the medium of powering chips and reading/stimulating neural tissue. For deeper brain stimulation, Khizroev and Liang went with magnetic fields on their magnetoelectric nanoparticles (MENPs). More recently, Sarkar’s team from MIT introduced Circulatronics, a fusion of electronics with cells controlled by near-infrared (NIR) fields. These feasibility demonstrations ignited excitement surrounding a new means to interact with the brain.

As motes get smaller, the theoretical endpoint is single-neuron or even synaptic resolution. Imagine allocating one mote per neuron - by injecting thousands of motes we’d be able to record or stimulate thousands of neurons simultaneously. We’d enable more precise decoding, more selective stimulation and even discern what is happening in numerous local circuits.

Although motes could be deliberately clustered in a particular region to capture local activity, alternatively, sprinkling it throughout the brain could capture activity from farflung brain regions simultaneously. For many brain functions (speech, movement, memory, mood), we’d be able to generate a picture that is more representative of the network-related activity underlying such functions, rather than activity from a localised brain region captured by typical deep brain electrodes, ECoG or the Stentrode.

A major practical advantage of this architecture is that it could reduce tissue trauma both during implant as well as in chronic use. Nanoparticles are injected directly into the brain, via bloodstream, nasal passage, or even by hitching a ride on immune cells, avoiding the surgical risk associated with conventional implants. Once in place, the ‘free-floating’ format may win over the larger, rigid devices, which often shear up against brain tissue during everyday movements of the brain. It is also suggested that the small size may be favourable for the chronic immune profile; the nanoscale of implants may elicit less of a foreign-body response.

Naturally, many companies spun out or set up to collaborate with these researchers. Fitting squarely into DARPA's Next-generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology (N3) program, neural dust’s commercialisation momentum has largely been spurred by this grant. Commercial efforts reflect the same technical fork from research efforts: ultrasound micro-implants (Iota), magnetic nanoparticle stimulation (Cellular Nanomed), and optical/nanoparticle concepts (Subsense).

The Berkeley neural dust project spun out into Iota Biosciences in 2017, before being acquired by pharma company Astellas in 2020. The original motes ended up being too large to be free-floating in the brain. Instead, the company turned its efforts to an implantable bladder device, with IDE approval granted by the FDA in 2024. Whether this technology includes the original neural dust concept is up to speculation. Their website mentions Iota's plan to showcase a ‘set of therapies’ to support brain recovery in 2026.

Also supported by the N3 program was Cellular Nanomed, led by Khizroev and Liang in their MENP-based BCIs. Recent headway has been using MENPs to ablate cancerous tumours, however BCI application remains largely preclinical in Khizroev’s lab. To date, news is quieter on Cellular Nanomed’s front.

After closing their $17M seed round, Subsense has emerged into the neurotech landscape as the leading company in ‘neural dust’ (although favouring the term ‘nanoparticle BCI’). Having forged a partnership with Ali Yanik’s UC Santa Cruz group and begun animal studies, one may guess the first-in-brain neural dust the world will see will be gold nanoparticles powered by NIR light.

As of now, no human trials for fully injectable nanoparticle BCI systems are underway. Although all looks encouraging in animals, like any good deep-tech innovation, small discoveries spur on new research directions to tackle core hurdles for human adoption.

Miniaturisation is constrained by physics, biology, and chemistry. As devices shrink, there is less room for electronics, memory, and on-chip processing, limiting chip complexity. For passive sensors, this is already a demanding trade-off. Smaller electrodes and interfaces also tend to produce weaker signals, making it difficult to maintain a meaningful signal-to-noise ratio. Increasing field strength is not a viable solution either. Physical limits cap how strong ultrasound or magnetic fields can be before they cause tissue heating. A workable balance may emerge, but it will likely require careful and non-trivial engineering.

Even if motes can be delivered less invasively than traditional implants, they still need to be positioned in the right place. Some researchers are engineering their particles with binding molecules to target specific neural cell types. Circulatronics goes as far as to chemically attach chips to immune cells, exploiting their natural tendency to hone in on inflamed regions.

Meanwhile, others like Cellular Nanomed are using magnetic fields to pull nanoparticles through to specific brain regions. After that, there comes the question of whether they will stay there? The nano nature of the motes may mean chips get sequestered by macrophages or microglia. They may accumulate, or drift away from their original positions. Ensuring direct positioning and staying will be critical hurdle to clear for the future of neural dust.

Another important consideration is what materials we are introducing to the brain. Nanoparticle coatings are a field of study in their own right. While coating materials such as gold are usually biocompatible, over time, these coatings may degrade and expose more harmful chemicals. Moreover, there’s room to understand what the effects of larger quantities of nanoparticles might do, especially if they accumulate.

A final major obstacle is the data transmission problem. If thousands of sensors are transmitting information at once, the bottleneck quickly becomes: how do you capture, synchronise and decode signals from thousands of sensors in parallel? The Neurograins team is addressing this with more complex sensors and more sophisticated data transfer protocols, improving structured communication at the cost of increased per-node power and system complexity. Even if the network works, the system still needs robust ways to track identity over time, knowing not only what a signal is, but which node produced it and where it is. Otherwise, “brain-wide dust” becomes hard to interpret.