Modern AI learns in the cloud, on racks of GPUs that draw kilowatts to megawatts, while the human brain learns continuously on about 20 watts, roughly smartphone power. A team at UT Dallas has moved a little closer to that biological efficiency, unveiling a lab-scale neuromorphic prototype that changes its physical synapses as it encounters new patterns. The group frames it as a small but concrete step toward on-device learning, guided by a brain-first design brief.

What makes the development impressive is just how the learning happens. Instead of updating numerical weights inside a software script, the prototype uses magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs) whose physical state represents synaptic weights. These MTJ synapses implement a Hebbian-style rule-“neurons that fire together wire together”-using the device’s natural randomness to make small changes, while storing each adjusted connection as a simple on/off weight for future use.

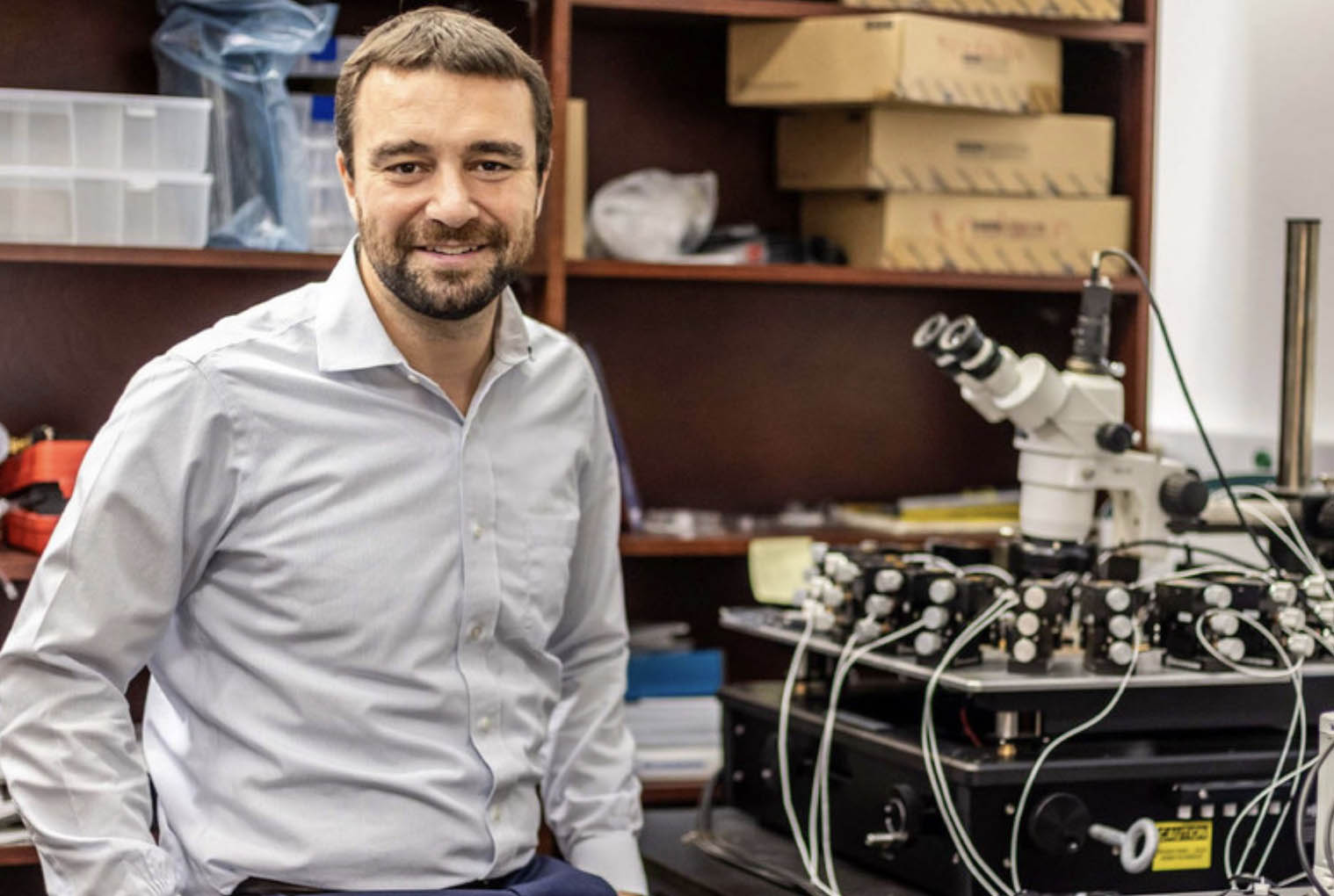

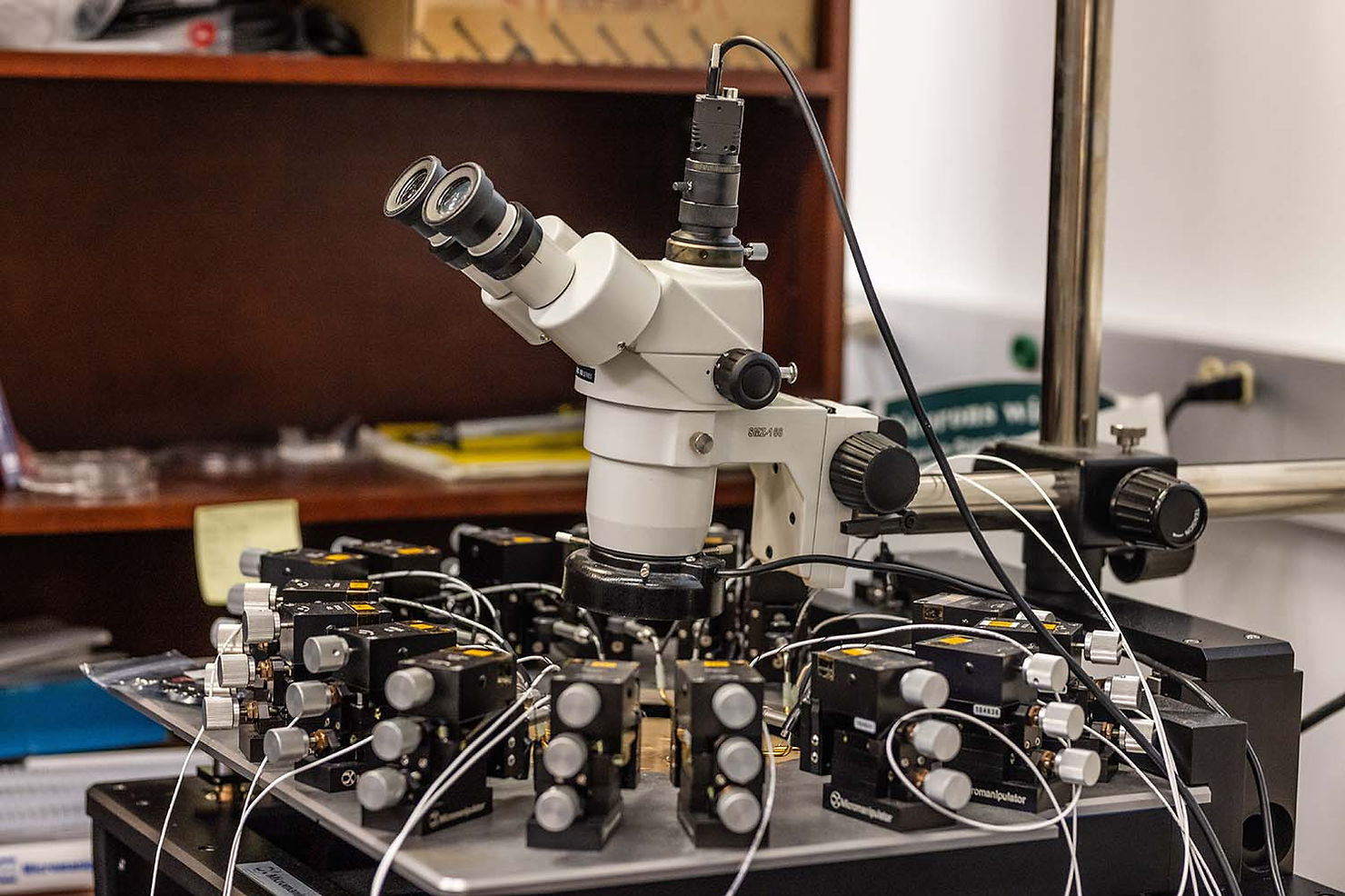

Last week, UT Dallas announced that Dr Joseph S. Friedman and his team at the NeuroSpinCompute Lab built a small neuromorphic computer prototype that learns patterns and makes predictions using fewer training computations than conventional AI systems. The work, involving Everspin Technologies and Texas Instruments as industry partners, is funded through several grants, including a recent U.S. Department of Energy grant to expand the research.

In a paper published in Nature Communications Engineering on Aug 4, 2025, Friedman and colleagues describe how their magnetic synapses store a simple, stable connection state for use and then adjust that state during learning when activity lines up. This follows a Hebbian idea that many will know from neuroscience: neurons that fire together wire together.

Each magnetic synapse, known as a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ), is built from two nanoscale magnetic layers separated by a thin insulating barrier. One layer has a fixed orientation; the other can flip when a small electrical pulse passes through. The alignment of those layers determines how easily current flows (parallel alignment for a strong connection, antiparallel for a weaker one), and that state is retained even when power is off.

During learning, brief current pulses use the device’s natural randomness to nudge the magnetic orientation toward or away from alignment depending on whether the connected signals fire together. In this way, the material itself stores and updates its connection strength based on its input, physically adjusting itself like synapses.

The result shows that a physical device can act like a learning synapse and that unsupervised, on-chip learning is feasible, albeit for now at a tiny scale. While the prototype does not yet show full system numbers that matter to products, like total energy per learning event, end-to-end speed, and behavior in larger arrays (the current array being 4x2), it is a solid milestone for brain-inspired computing.

In most AI systems today, learning happens in big data centers. Software updates the strength of millions of connections by moving numbers back and forth between memory and processors, which takes a lot of power and time. Once trained, the model is usually frozen and sent to devices for use. That is efficient for running decisions, but it does not let the device keep learning on its own. Nor is it particularly environmentally friendly.

For neurotechnology, the shift to neuromorphic opens concrete avenues. Intracortical and surface decoders could adjust to day-to-day signal drift without lengthy recalibration, aligning with how labs chase stable control across sessions. Closed-loop neuromodulation could iteratively tune stimulation patterns within a session as physiology changes, rather than relying on presets that age quickly. Wearables for attention, fatigue, or motor intent could build and update user-specific models locally, keeping raw biosignals private while cutting bandwidth and latency.

Does this point toward higher or “general” intelligence versus today’s generative AI? Not on its own. The UT Dallas work demonstrates local Hebbian learning in physical synapses, which is important for efficiency and continuous adaptation, but it is not a general-purpose reasoning engine or a replacement for transformer-style training at scale.

In short, the near-term value for neurotech is practical: devices that adapt where they operate and do so within strict power limits. If future arrays scale while keeping their stability, they become building blocks for systems that learn as they record and stimulate, which is the kind of progress that matters at the bedside and on the body.