Billions of synapses simulated. Millions of neurons modeled. A single calculation that would take a human 12.7 billion years, completed in seconds by a machine. The race to digitize the brain has become a benchmark for the power of modern supercomputing, and a flashpoint for how neuroscience defines progress.

Neurotechnology is entering an era shaped by high-performance computing. From flagship simulations at Fugaku and Argonne to neuromorphic experiments across Europe, cortex mapping has become a proving ground for the limits of hardware and the ambitions of brain science. What does this surge in digital modeling mean for research, medicine, and the future of neurotech?

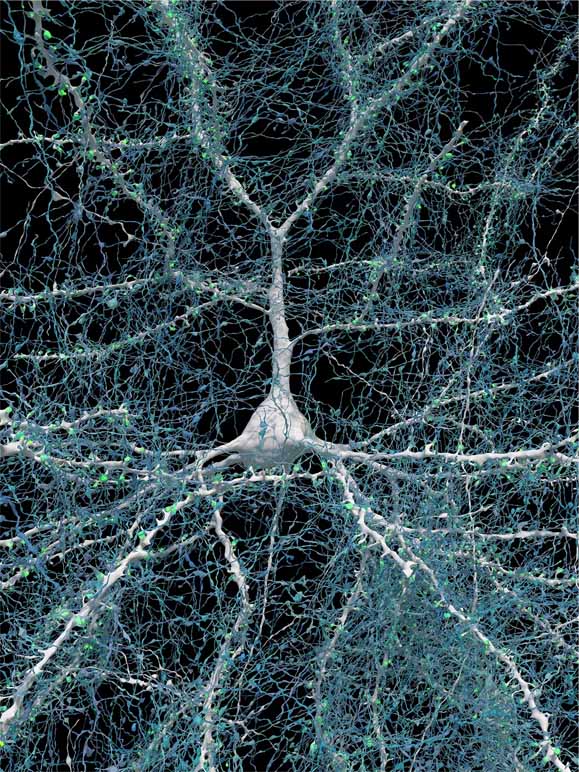

Mapping the mammalian cortex involves modelling millions of neurons and hundreds of billions of synaptic connections at extremely fine spatial and temporal resolutions. Doing this faithfully requires processing capacity orders of magnitude beyond what standard lab computers provide, which is why mostly national labs and flagship initiatives have thrown money and compute at the problem. In November 2025, researchers used the Fugaku supercomputer to simulate a cortical slice containing 10 million neurons and 26 billion synapses, running on 158.976 nodes and executing 400 quadrillion operations per second.

A human with a calculator would need 12.7 billion years to perform the same number of operations. These feats of engineering are impressive, but they are often presented without context. They do not mean we are close to simulating a human brain, and they do not automatically produce clinically actionable insights.

Large‑scale simulations such as the Fugaku cortex run show what is technically possible. The supercomputer mapped 86 cortical regions and allowed researchers to explore how microcircuits might self‑organise. However, these simulations rely on simplified models of neurons and synapses; they compress complex biochemical interactions into computational rules.

Even then, scaling from a slice to a whole brain is daunting. HPCwire reports that imaging and segmenting just one cubic millimetre of brain tissue yields about 2 petabytes of data (2000 terabytes), and analysing it with an exascale supercomputer takes several days. Extending this to a one cubic centimetre mouse brain would require ~3 000 days; applying the same approach to a human brain (roughly 1 000 times larger) would take 3 million days (8213 years).

Current resources thus cannot support whole‑brain connectomics at cellular resolution. The sheer size of the dataset also raises questions about energy consumption and environmental impact; even proponents of large‑scale simulations acknowledge that their carbon footprint must be addressed.

Europe’s Human Brain Project (HBP), launched in 2013 with €1.2 billion of funding and involving 256 researchers, aspiring to build a detailed virtual human brain to accelerate drug discovery and systems neuroscience. Its roots lay in the Blue Brain Project, which famously simulated a neocortical column with 30 000 neurons. However, critics argued that the project’s management prioritised building a flagship supercomputer over funding diverse research, prompting over 260 scientists to sign an open letter protesting the HBP’s top‑down approach.

Neuroscientist Peter Dayan likened the effort to copying brain hardware without understanding the software. Even within the models, data scarcity looms: a cortical microcircuit can form 2 970 possible synaptic pathways, yet only 22 have been characterised experimentally. HBP leaders responded by investing in predictive algorithms, but the gap between data and model remains.

When EU funding wound down in 2023, the Blue Brain team open‑sourced 18 million lines of code and several petabytes of data, shifting the work to the non‑profit Open Brain Institute. Such transparency is commendable, yet it underscores the question: what did a €1.2 billion bet on supercomputers actually yield for medicine or neurotechnology?

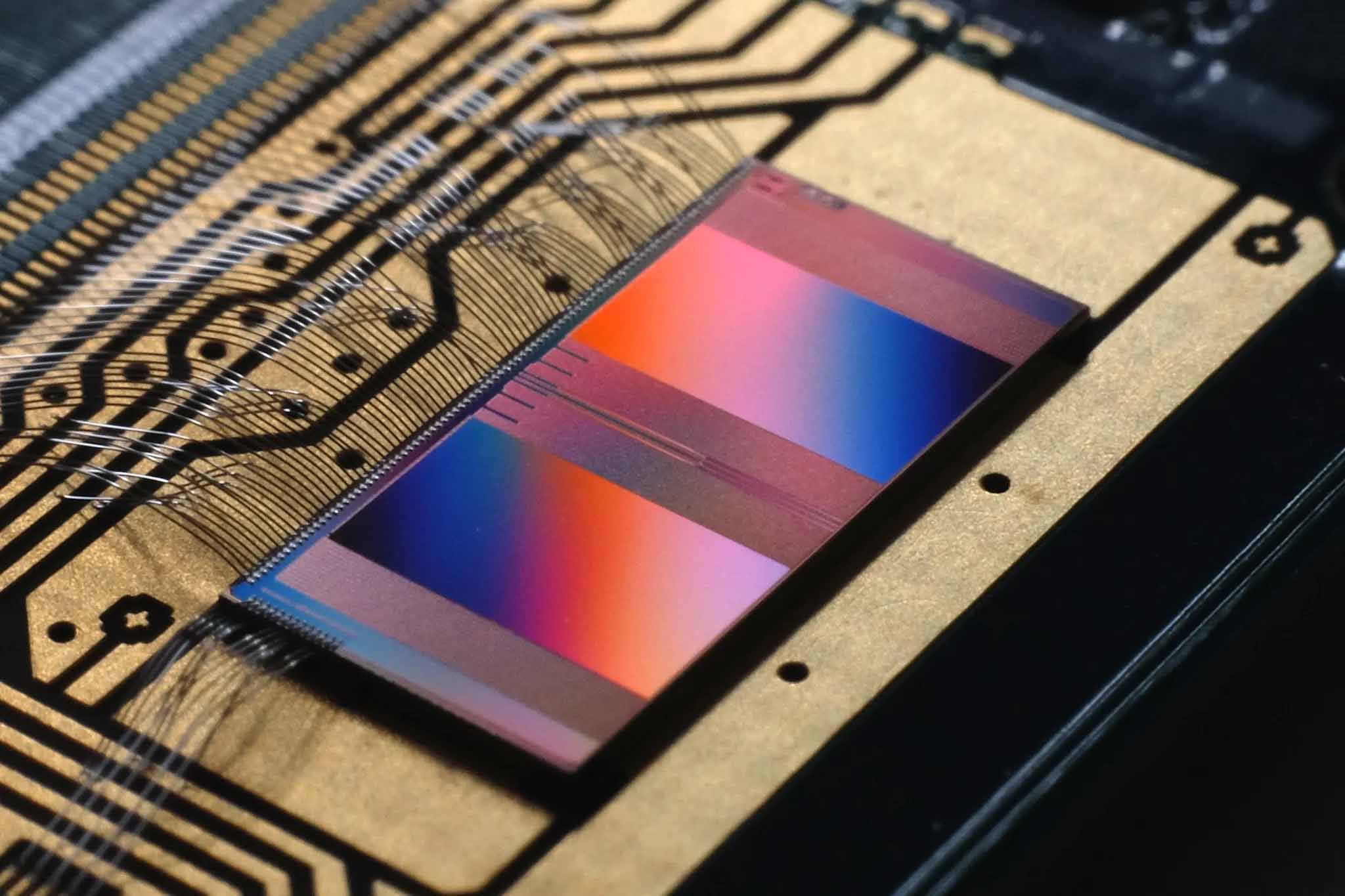

Recognising the limits of brute‑force simulation, some initiatives are exploring neuromorphic computing; hardware that mimics the brain’s architecture to achieve energy‑efficient computation. As part of the HBP, engineers and IBM collaborated on a system with 4 million artificial neurons and one billion synapses, aiming to provide a platform for cortical experiments by 2023.

Neuromorphic chips can simulate spiking dynamics orders of magnitude faster per watt than traditional supercomputers. However, their capacity is still far below biological brains, and programming such systems remains a challenge. Meanwhile, connectomics projects are experimenting with targeted mapping: focusing on specific circuits involved in disease rather than whole brains. This approach generates more manageable datasets and is more likely to yield near‑term therapeutic insights.

The case studies above illustrate a recurring theme: technological achievements are often conflated with scientific understanding. Simulating millions of neurons at petascale does not necessarily explain how cognition arises or how to treat disease. More importantly, data quality and interpretability are as crucial as computational power.

The fact that only 22 of 2 970 synaptic pathways in a microcircuit have been experimentally characterised implies that many parameters in large models are based on assumptions rather than measurements. When models with billions of assumptions produce predictions, those predictions are likely reflecting built‑in biases.

Energy consumption is another ethical issue; the environmental costs of running exascale simulations may outweigh the benefits. Neurotech startups should be aware that investing in targeted, hypothesis‑driven experiments and energy‑efficient computing could yield greater returns than partnering with high‑profile simulation projects.

Supercomputers can still play a key role. They are invaluable for processing high‑resolution imaging data and for testing mechanistic hypotheses at scales unattainable in vivo. They also drive innovation in hardware and algorithms that can trickle down to more accessible platforms. However, expectations must be realistic. Building a ‘digital brain’ is not the same as understanding the brain, and success should be measured by whether these models inform practical tools, such as neuromodulation devices, diagnostics or drug discovery, rather than whether they can scale to a certain number of neurons.

Case studies like the Fugaku simulation demonstrate what is possible when computational resources are concentrated; the Human Brain Project shows the dangers of focusing on hardware at the expense of diverse science; and the neuromorphic approaches illustrate the promise of alternative architectures. There is a strong incentive to focus on initiatives that produce actionable insights with transparent assumptions, recognise the environmental costs of computing and cultivate collaborations that prioritise patient impact over raw teraflops.

[Cover image: "BrainScaleS-2 neuromorphic single chip" by Heidelberg University]